Distributed Realtime Server Architecture

Here you go, free TL;DR. Interested?

Storytime#

The other day, I decided to learn about WebSocket/realtime applications. I had known about them for the longest time but had not written a single line of WebSocket code. I kind of knew what it is about, something about chat applications, but didn’t know how it works.

I heard about Ably from Theo. Theo is the CTO of Ping. He talks about web development and software development in general, you can find him on Twitch streaming or watch the cuts on YouTube. I remembered he said something along the lines of, if he was going to make a realtime app, he would use Ably or PubNub, Pusher rather than doing it from scratch. Or he could use Socket.io because he didn’t know anything more popular than that. Of course, I didn’t know what’s the differences, so I went scavenge on Google and landed on Ably.

It’s a realtime platform as a service. You use Ably services to do realtime things, like making a chat app or a game, or broadcasting a match or something like that. But, they present those things on their website in a super generic way, and I had no idea what Ably was technically. Is it a WebSocket server? Is it a complete solution? Is it some kind of enterprise super-scale thingy like AWS?

To be honest, I don’t know how I figured out that Ably provides channels that we can pub/sub to and Ably Queues is a Message Queue, so without further ado, let’s dive into the architecture overview.

Architecture Overview#

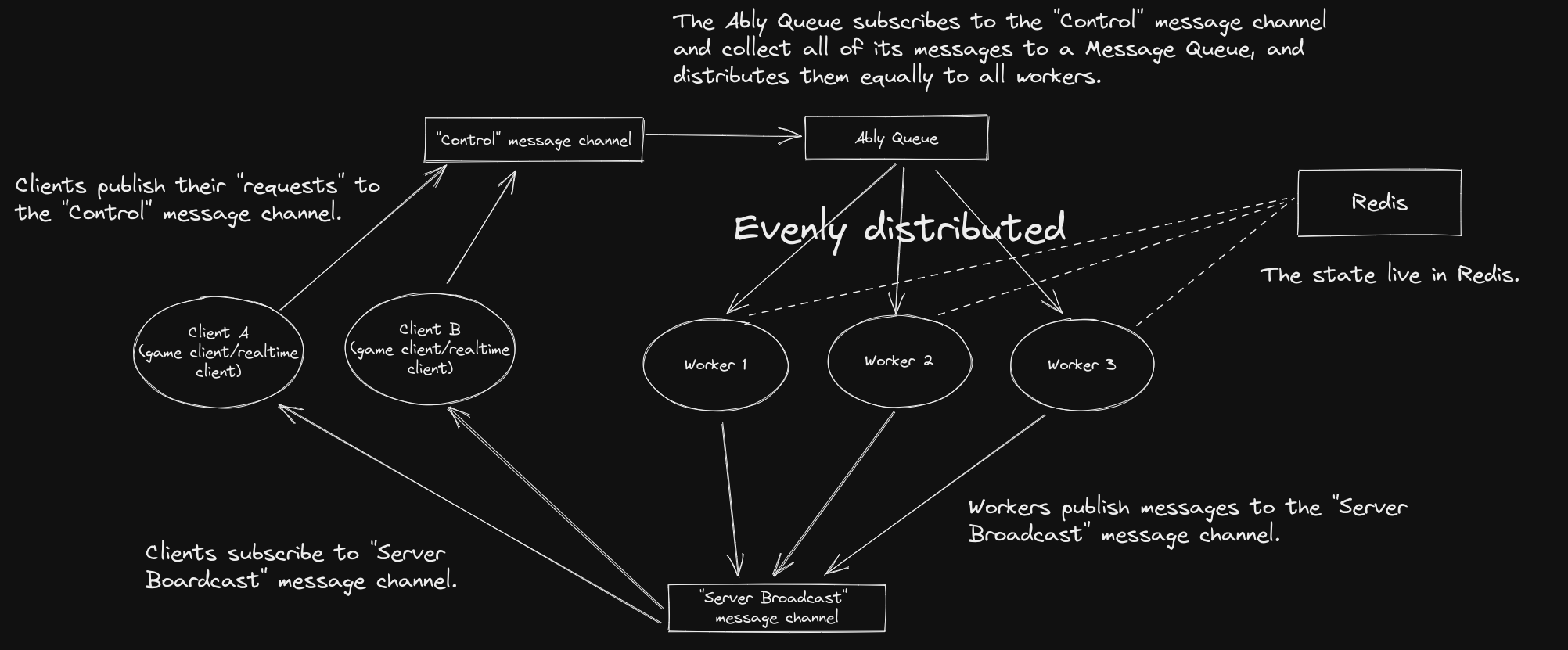

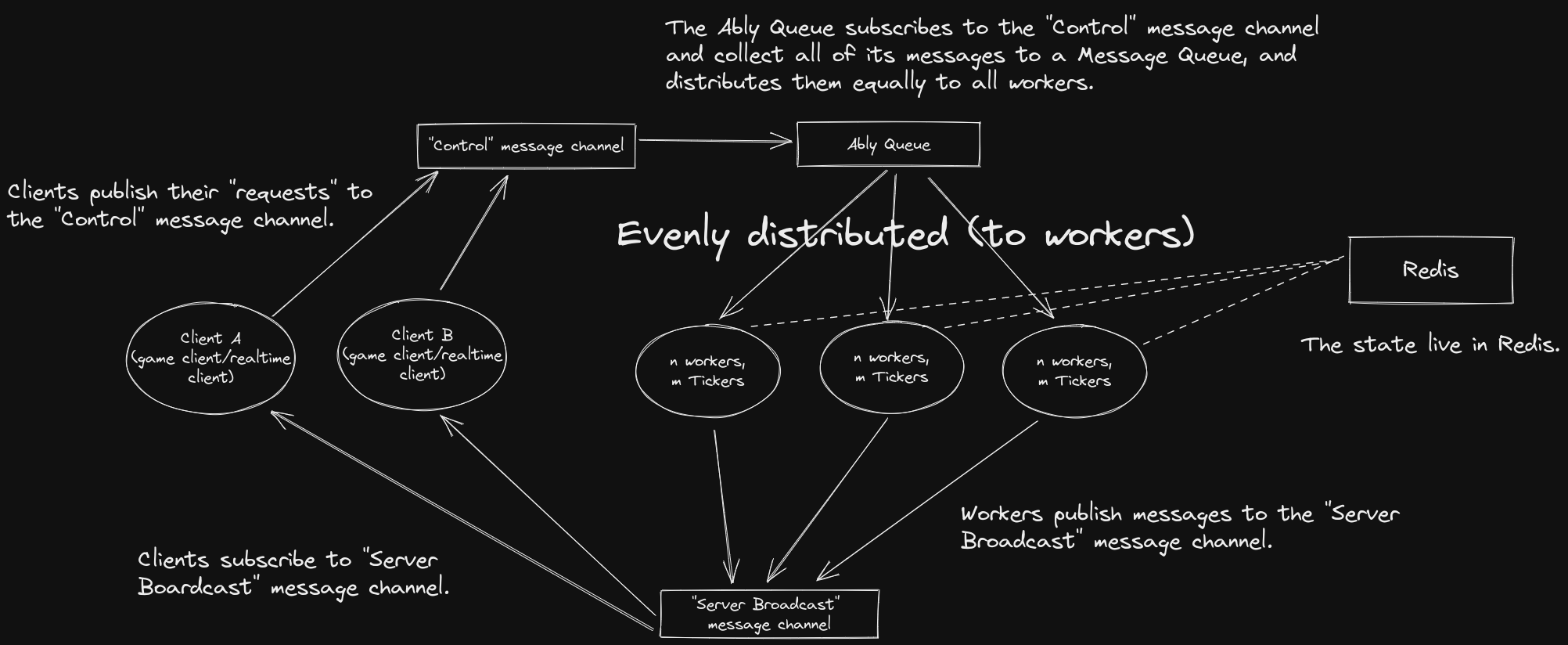

We can start with the clients. The clients are, for example, the browser chat app or a game client. They publish messages to the “Control” message channel, something like player movement controls, or chat messages. The only subscriber that subscribes to the “Control” message channel is the Ably Queue (you can set it up so that publishers can only publish but not subscribe to a channel). Ably Queue is a thing that takes messages from a message channel (among other sources) and puts them in a queue, awaiting their destinations.

Ably Queue ensures that a message only goes to one subscriber exactly once. Technically it’s hard, but seems like they can be done. What I care though is the fact that messages are evenly distributed to its subscribers, i.e. our workers. Because of that, we can design our workers to be stateless so that it doesn’t matter which worker receives the message. The state lives in Redis, which all workers share.

The workers, after processing the “Control” messages, will publish the “response” to the “Server Broadcast” message channel. They of course will have the option to not send any message at all, send one, or send many messages. These messages will be broadcast to all clients.

But, what if we want to send a message to a specific client only?

Ah. Two options, you can either send the messages to a private message channel that only the recipient subscribes to, or you can encrypt it in a way that only the recipient can decrypt.

Demo#

I made a Tic Tac Toe game that implements this architecture.

The Next.js frontend “Client” GitHub repository

The Go worker GitHub repository

The “Ticker” extension#

Often times there will be a timer that counts down things if you’re making a game. In a turn-based game, it might be the turn’s countdown timer or a match timer. In a more realtime game like Counter-Strike Global Offensive, it might be the time of a round, about 2 minutes.

Let me introduce you to a familiar unit of time, called “a tick”. It’s just like a second, or a minute, or an hour, or a day. The thing we want to invoke after each time a tick passes is called a Ticker. For context, CSGO’s dedicated server can be 64 or 128 ticks per second. Minecraft servers are 20 ticks per second (or at least they try to be).

So, a Ticker does just that. It runs some code every time a tick passes. It’s a continually running thing, 24/7. But our Tickers have a special trick up their sleeves: they can also share their workload. What I mean by “sharing workload” is, if you have 100 Tickers and 500 game matches running, each of our 100 Tickers will all go and pick a game match that needs ticking, then take their time to do their job. They pick from a cluster of 500 game matches. No single Ticker is associated with any specific game match. If Game Match A is picked and being ticked by Ticker 1, then the other 99 tickers will know to go and pick Game Match B, Game Match C, etc.

Immediately after ticking a game match, the Ticker will go and pick the next one, if any game match needs ticking at that moment. They can also go into Idle Mode if there’s no job to do after a while. The process of picking a game match to tick, which includes Locking, Ticking, Scheduling, Idling etc. is pretty complex. Check out the source code for the worker (which also includes the package for the Ticker) to get to the nitty-gritty.

Of course, you can have 500 Tickers 500 game matches, or 1 Ticker 500 game matches, or 1000 Tickers 1 game match. That depends on the time it takes to run the logic code each tick, and the consistent timing of the ticking that you tolerate (because Tickers are going picking game matches, not scheduled to do so).

Retrospect#

I’m pretty new to the world of distributed and realtime thingies. There are problems that I encountered like Locking, but I didn’t grasp the full picture yet. Though, it was a good learning opportunity.

This motivated me to make an Architecture browser, like a library of architectures laid out in some easy-to-understand way. They must be practical and relevant in this modern world. There are modern solutions to solve old problems, and as an emerging citizen of an emerging new world, I want to document and elaborate on things happening just to stay informed in some way.